Want to be notified as soon as we publish new content like the Quick Think? Subscribe here.

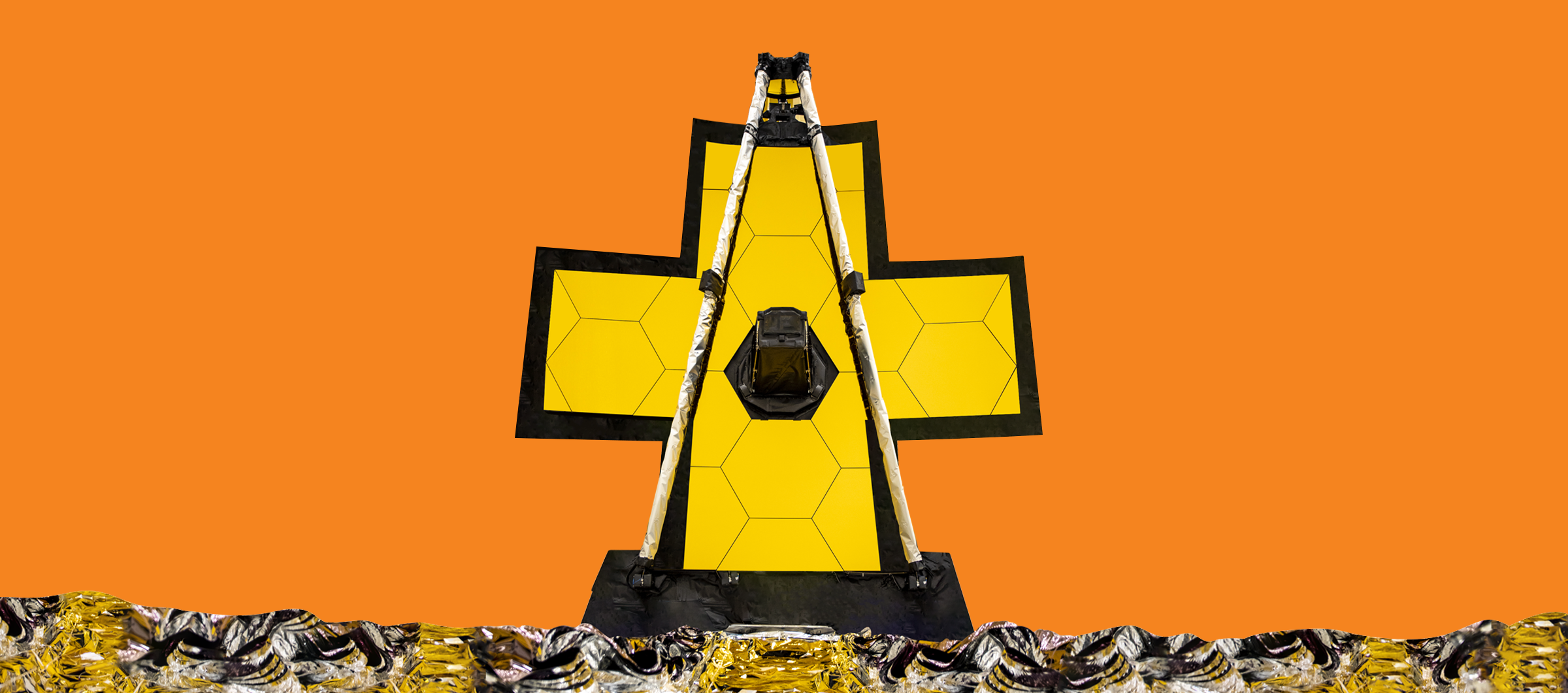

The Big Story: The NASA Engineer Who Made the James Webb Space Telescope Work

“Greg Robinson turned a $10 billion debacle into a groundbreaking scientific mission. He had two priorities when he took over. The first was reducing human error.”

What it Means for You

In soul-stirring images, Robinson’s achievement shows us that “obsession with getting the little things right is how big things happen.”

It is a celebration of the power of the unsexy work that produces extraordinary outcomes, even for the most complex undertakings.

Milestone, high-visibility events – the big announcement, the big media push, the big ad buy – are key leadership and communication moments to be approached energetically and strategically, of course. Sexy stuff.

Yet it’s the day-to-day work, the undistracted commitment to an operational priority communicated through an unwavering drumbeat message campaign, that gets the big jobs done.

Let’s pull back the lens just a bit and look at (at least) two down-to-Earth lessons we can draw from the achievements of Robinson and his remarkable NASA engineers…

1. Communications

It’s the often-unsung communication efforts that make the difference. The conversations and information sharing that happens in huddles, patient rooms and on the third screen of the intranet at the nurse’s stations.

This is the “routine” work of communications that is at the heart of successful operations. It’s how complex organizations change. It’s the rebar of the work you do.

Three additional thoughts, here:

Words. The words matter, of course. You must clearly articulate standards and expectations, what you do and how you do it and why you do it.

In an interview with us in 2019, Lee Health CEO Larry Antonucci, MD, MBA, shared his approach to medical errors when he took over the reins of one of Florida’s largest public health systems. He told us:

“When I came on board, we were talking about hospital-acquired conditions and harm. Our goal was to get to the 75th percentile. I said, so our goal is to create as much harm as 25 percent of the hospitals in the country? I said that our goal should be zero harm, period. Everything else is a reference point, not a goal.

This caught on and completely changed how we thought about everything. If we change our thinking and say zero, then we’ll come up with a way to make that avoidable. It was remarkable. Within a year, we turned the whole concept around by just pivoting a little bit on the terminology.”

“Pivoting…on the terminology”? Said another way, they successfully reframed the effort, the need and the result by changing the words.

But words alone are not enough, of course. Consider these two factors:

Focus. A communications campaign can only be successful if the story is told over and over, a message consistently delivered through multiple channels over many months or years.

If it’s a message of the month – if leadership is likely to jump at the next squirrel that darts across the lawn and changes priorities and messages – better to have said nothing at all.

Clarity. If everything is important, nothing is, really. In healthcare, few things are truly unimportant, but some things must be a priority. Clearing the communication airwaves so your key messages can be heard is key to success and sometimes the hardest challenge.

A great communication campaign lost in the fog of other competing, equally great communication campaigns is a lost investment of time, money and opportunity. A successful campaign requires the political strength to say “Yes” to a few things and “No” to most others.

2. The power of priorities

This was demonstrated in Robinson’s decision and commitment to focus on reducing errors as his NASA team built one of the most complex machines ever constructed.

“In Mr. Robinson’s first month on the job, something unfortunate happened: The fasteners on the sunshield popped free. It was classic human error. A bunch of loose screws and washers proved to be an early test of Mr. Robinson’s philosophy, and he responded by ordering a comprehensive audit of the entire system from every possible angle. The designers, contractors and engineers independently checked the paperwork against the hardware and compared their notes to identify and solve problems before they metastasized—the NASA equivalent of a colonoscopy.

“’We found a few things that needed moderate changes,’ Mr. Robinson says with an engineer’s understatement.”

You know about the focus on reducing errors, of course. You have clinical quality teams, M&M conferences, harm reduction programs and more.

And yet, healthcare “has failed to make significant progress on eliminating preventable medical errors” since 1999, according to an article this week in Becker’s. Our industry understands the lessons taught by Robinson’s steady, relentless focus on improvement. But there’s so much work to be done towards applying them.

How did Antonucci and Robinson achieve success? It took – and it takes – clear lines of communication, leadership’s willingness to focus and trust by all involved. And, critically, people who are willing to sit in the background, ask the hard questions and stay on track.

Such focus helps prevent “a whack-a-mole” approach to error reduction, per the Becker’s article.

It keeps people, teams and organizations pointed towards the end goal – launching a groundbreaking telescope and materially improving lives. It provides stability in times of stress and confusion, an anchor for others to look to for a reference point. It creates rigor and discipline.

Unsexy? Yes. But better to get it right than to look good.

This piece was originally published over the weekend in our Sunday Quick Think newsletter. Fill out the form to get that in your inbox every week.

Subscribe to Jarrard Insights & News

"*" indicates required fields