Note: This piece was originally published over the weekend in our Sunday newsletter. Want content like this delivered to your inbox before it hits our blog? Subscribe here.

2-minute read

The Big Story: Staffing overtakes financial challenges as top concern among hospital CEOs, survey finds

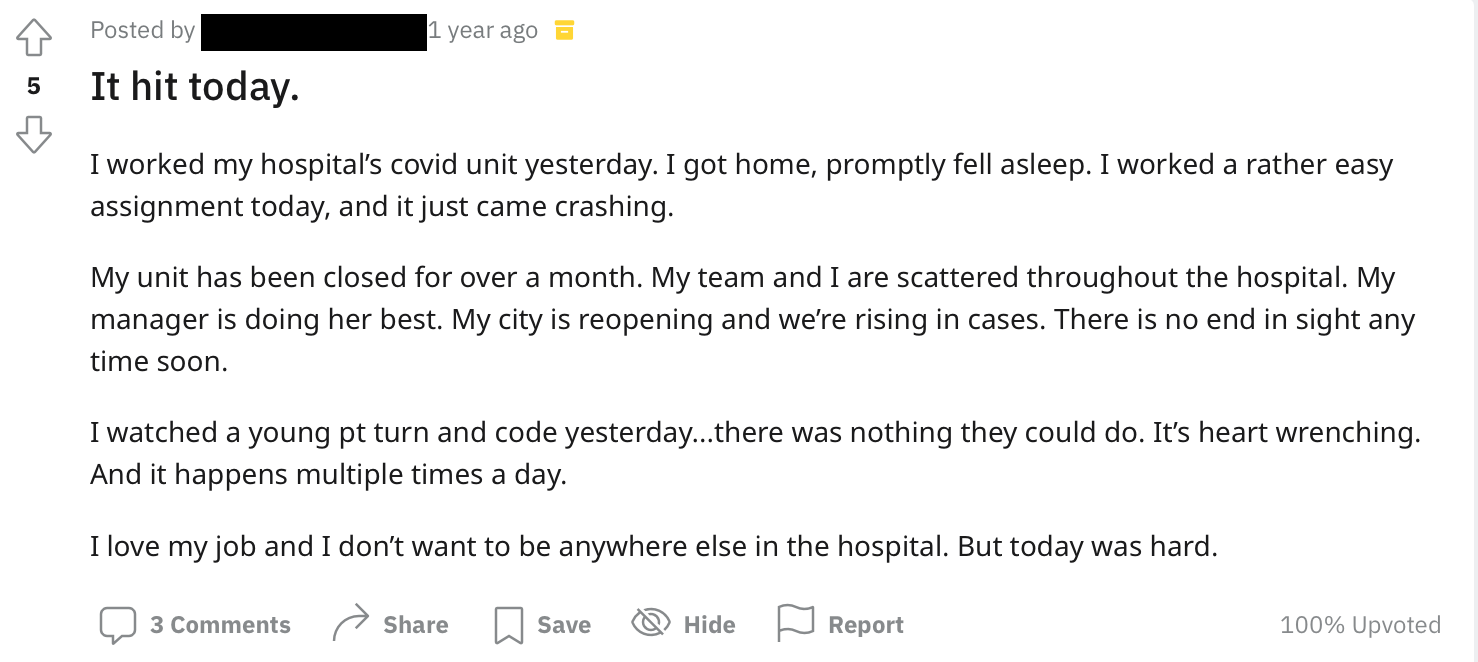

The workforce shortage is perhaps the biggest topic of conversation across the industry right now. While some providers and staffing agencies are offering large sign-on bonuses, others are going for retention bonuses and raises. Everyone is trying to staff up, whatever it takes. Many, especially but by no means exclusively rural hospitals, are barely hanging on.

What it Means for Our Healthcare System

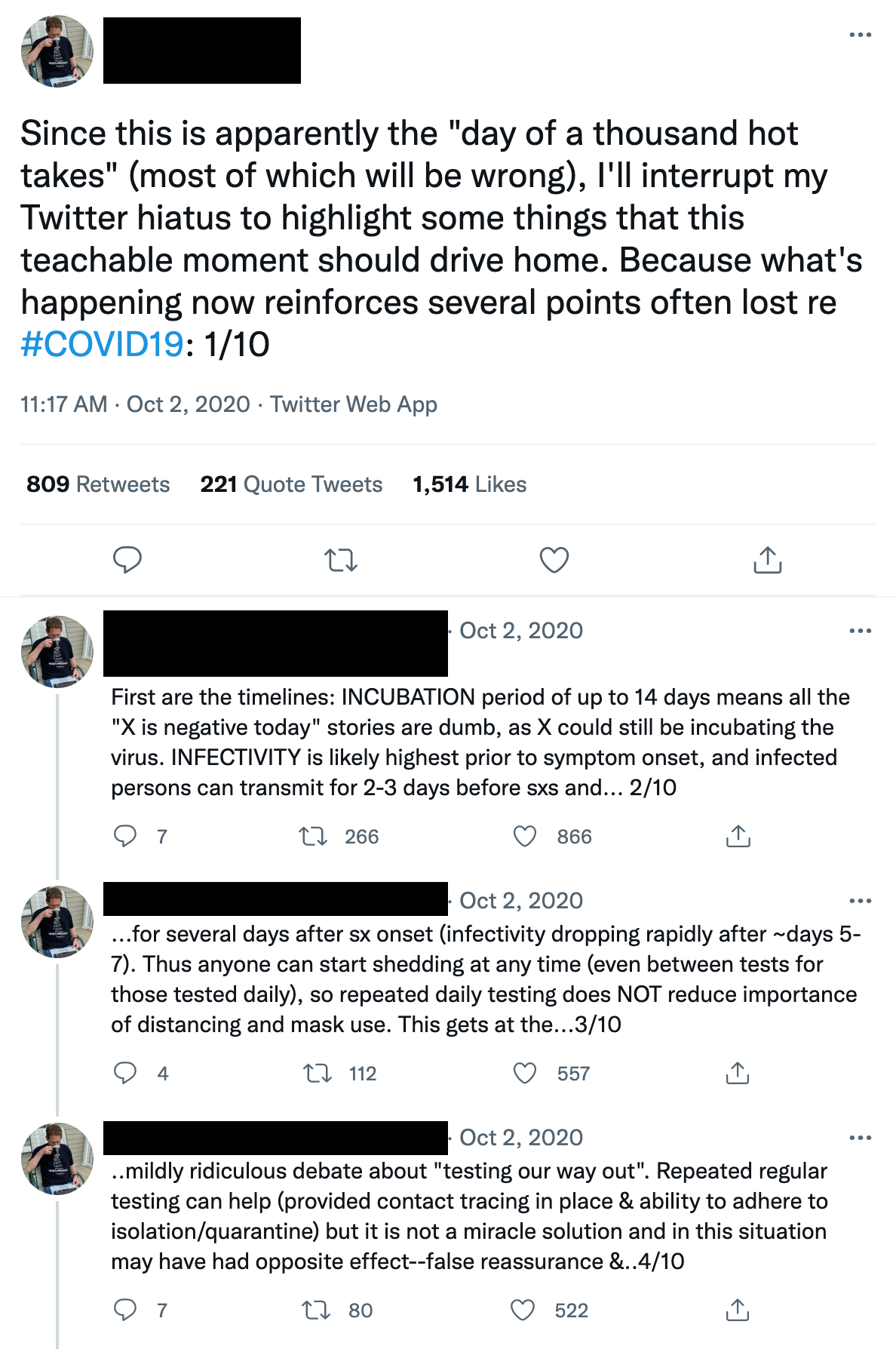

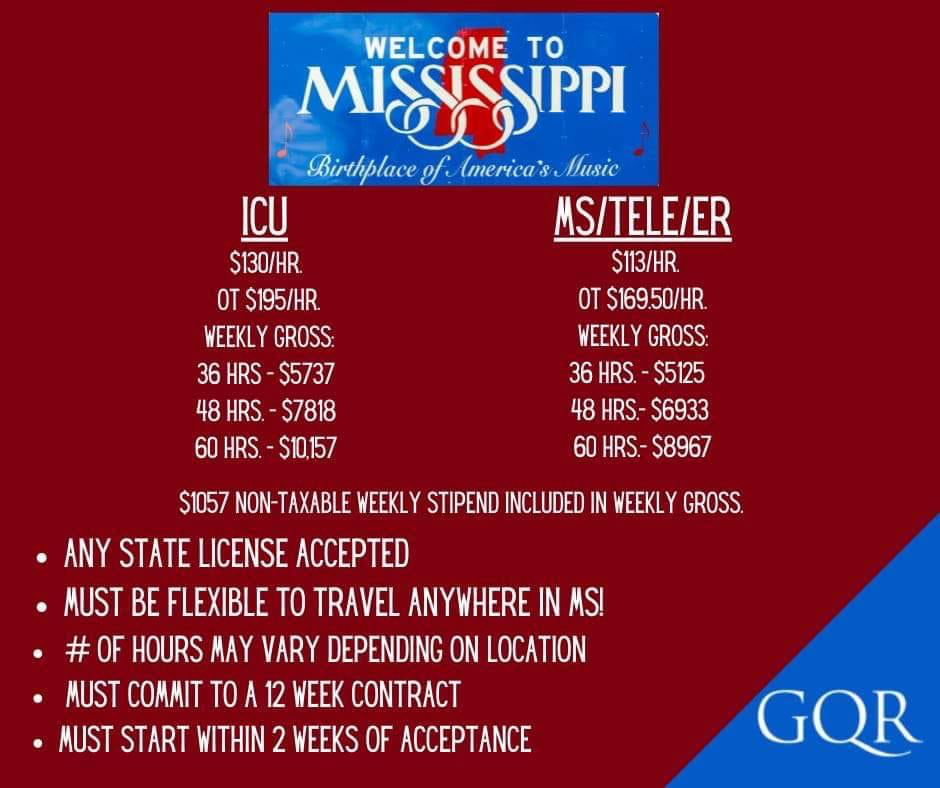

Pandemic shortages accelerated the growth of temp and travel nursing, effectively changing the compensation model for RNs. That’s created a feedback loop where the shortage has become both cause and effect. Hospitals can’t maintain the tab for travel nurses – yet many can’t properly staff up without them. The jaw-dropping $40,000 signing bonuses are stopgap and not sustainable.

Dawn Carter, a veteran healthcare strategist and founding member of the Rural Healthcare Initiative, likened the situation to The Lorax, Dr. Seuss’ foray into environmentalism that describes the dangers of overusing a resource to the point that it disappears. We need nurses, and they deserve to be well-compensated. Full stop. It’s incumbent on us to design a system that allows that to happen. A system that sustains the forest.

While many are working feverishly to discern the long-term foundational changes necessary to compensate caregivers what they’re worth while keeping labor costs manageable, the land-grab nature of the current healthcare recruitment push continues. And it just might be catastrophic for smaller providers who can’t keep up.

We’re not parachuting in with 750 words to solve a very complex problem. But we do think Carter’s insight on how provider organizations, particularly rural and independent hospitals, might mitigate the damage now with their existing staff – is imminently shareable. Her suggestions cover both tactical interventions and messaging.

An extra week off. Literally, give your staff an extra week off. Maybe two. More hospitals are taking this approach because that time away may help with burnout and is a relatively low-cost benefit to the employee. Many hospitals are already offering other smart benefits – subsidizing gym memberships, meal delivery services and so on. But if we’re talking about people who are thinking about leaving, giving them extra space to recharge may be a wise step towards keeping them.

Professional development. What else can your employees do? Whatever it is, show them that. From the moment they first consider a healthcare career through their entire time with your organization, make clear the ways a team member can grow in the job or grow into another one. Many hospitals are already helping finance additional technical/educational investments. They should make those opportunities known.

Carter cited a speaker from last week’s South Carolina Hospital Association virtual meeting who suggested hospitals ensure that high school students understand the low-cost path to a high-paying job. Someone paying two years of technical college tuition and coming out of it with an RN can enter the market making $60,000, but there’s the potential for $200,000+ by pursuing a CRNA.

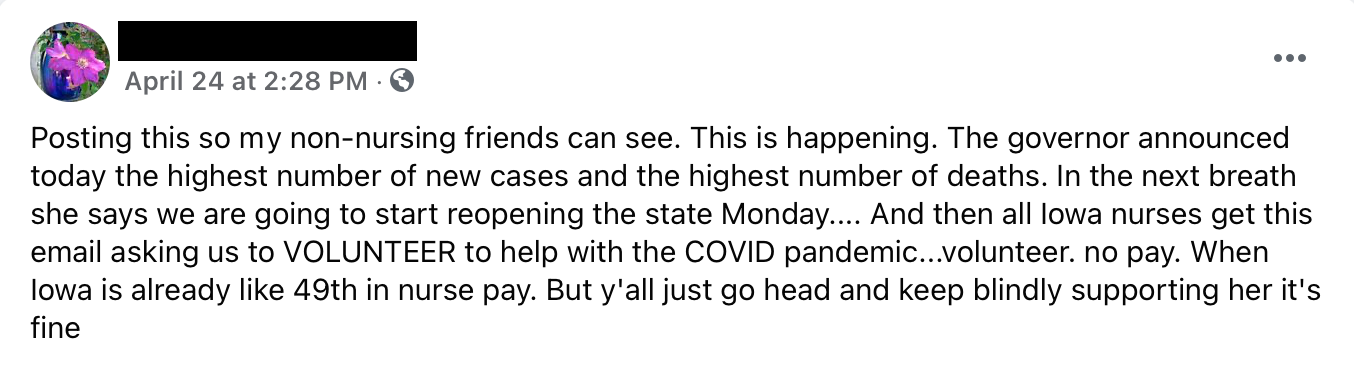

Clarity. Carter noted that much of the money paying for those stopgap measures like travel nurses is stopgap funding (federal stimulus and relief dollars). It’s temporary. This is an important point to make when addressing staff nurses who are justifiably frustrated seeing the compensation packages for their traveling peers while they’re receiving far lower raises/bonuses. Hard conversation, but it’s worth sitting down with staff to really talk about the current dynamics and explain why those levels of compensation aren’t sustainable as the one-time relief funds run out. Yes, you’ll still hear questions about why that one-time money is going to temps and not staff, but it will hopefully provide helpful context.

Connection with leadership. The critical message is that the core problem is a broken system, not uncaring leadership. This is no time to be defensive and complain about trying to operate a hospital in today’s brutal environment, especially with nurses who’ve been stretched beyond reason by the past two years. The point, rather, is to have deep, heartfelt conversations with staff about leadership’s position on the issues and the various imperatives they’re balancing.

To imbue those messages, Carter underscored the enduring value of leader rounding and one-on-ones. Find time to build relationships with staff, listen to their concerns and show genuine humanity. Sometimes that means telling your own story, too. We’ve heard from clients whose leadership spoke during town hall meetings about their toughest moments during the pandemic. Showing that level of vulnerability was powerful and helped dampen some of the tension that had been building.

Note that these conversations shouldn’t be used as distractions from or substitutes for practical interventions. They should be a supplement, a way to both solicit helpful information about what staff need and to demonstrate that you and the organization are working towards a collective solution.

This piece was originally published over the weekend in our Sunday Quick Think newsletter. Fill out the form to get that in your inbox every week.

Subscribe to Jarrard Insights & News

"*" indicates required fields