Introduction

“No go, unfortunately.”

That was the text from a friend saying her spouse, a physician, wouldn’t talk to us for this piece.

As a critical care physician who spent the last 18 months treating COVID-19 patients, he’s now taking an extended sabbatical to recover. He had the perfect perspective for an article looking at the current state of the healthcare workforce – the accelerated burnout, the frustration, the fear and the sheer exhaustion.

We had questions lined up: What do doctors and nurses need today? How much does monetary compensation play into the equation versus other types of support? Do the rumblings about an exodus from healthcare represent a real threat? Where do you hope to be after your time away?

But no, we would not be asking those questions. And maybe, that makes the story more powerful.

That this elite physician couldn’t talk to us wasn’t a matter of scheduling. It was because he has given everything to save as many people from COVID-19 as possible and has nothing left.

“He just shuts down when we talk about COVID,” the spouse said. That exhaustion encapsulates the problem our entire healthcare system is facing today. It clarifies both the human cost and the operational challenges facing provider organizations.

As an industry, we’ve been talking about the burnout of our nurses and physicians for years, to the point of cliché and numbness. Then: COVID. And now? The headlines are everywhere:

- Mississippi’s nurses are resigning to protect themselves from Covid-19 burnout

- Burned out by the pandemic, 3 in 10 health-care workers consider leaving the profession

- U.S. hospitals hit with nurse staffing crisis as pandemic rages on

- 153 people resigned or were fired from a Texas hospital system after refusing to get vaccinated

On top of that, President Biden’s new mandate for large employers will force even more people to make a choice – including some healthcare workers who may join peers who have already decided their career isn’t worth the vaccine.

All told, addressing the exhaustion and resignation of our clinicians has become an urgent business imperative for every organization who employs physicians and nurses. The issue’s been building for years. Maybe you can momentarily stanch the bleeding with pay raises and travel nurses, but that won’t heal the wound.

What to do now? This report, based on interviews throughout the Jarrard Inc. network of clients and experts, triangulates the trends, draws conclusions about the future and offers thinking on how to manage an issue that’s gone past the boiling point.

BY THE NUMBERS

Employees lost by Southern hospitals

Healthcare workers experiencing burnout

Healthcare workers considering leaving the industry

Healthcare workers self-reporting anxiety or depression

Back to the Beginning

Graepel

Burnout and the growing shortage of healthcare workers are well-documented. National surveys from a couple of years ago revealed burnout rates approaching 50 percent for a variety of reasons, per Kirk Brower, MD, chief wellness officer at Michigan Medicine. Long hours, burdensome administrative requirements, mediocre technology all contributed. Kevin Graepel, MD, PhD, a pediatric resident at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, observed that the buildup starts early. “A lot of the challenges my colleagues and I are facing in terms of burnout are driven in large part by the way resident training occurs in the U.S.,” he said.

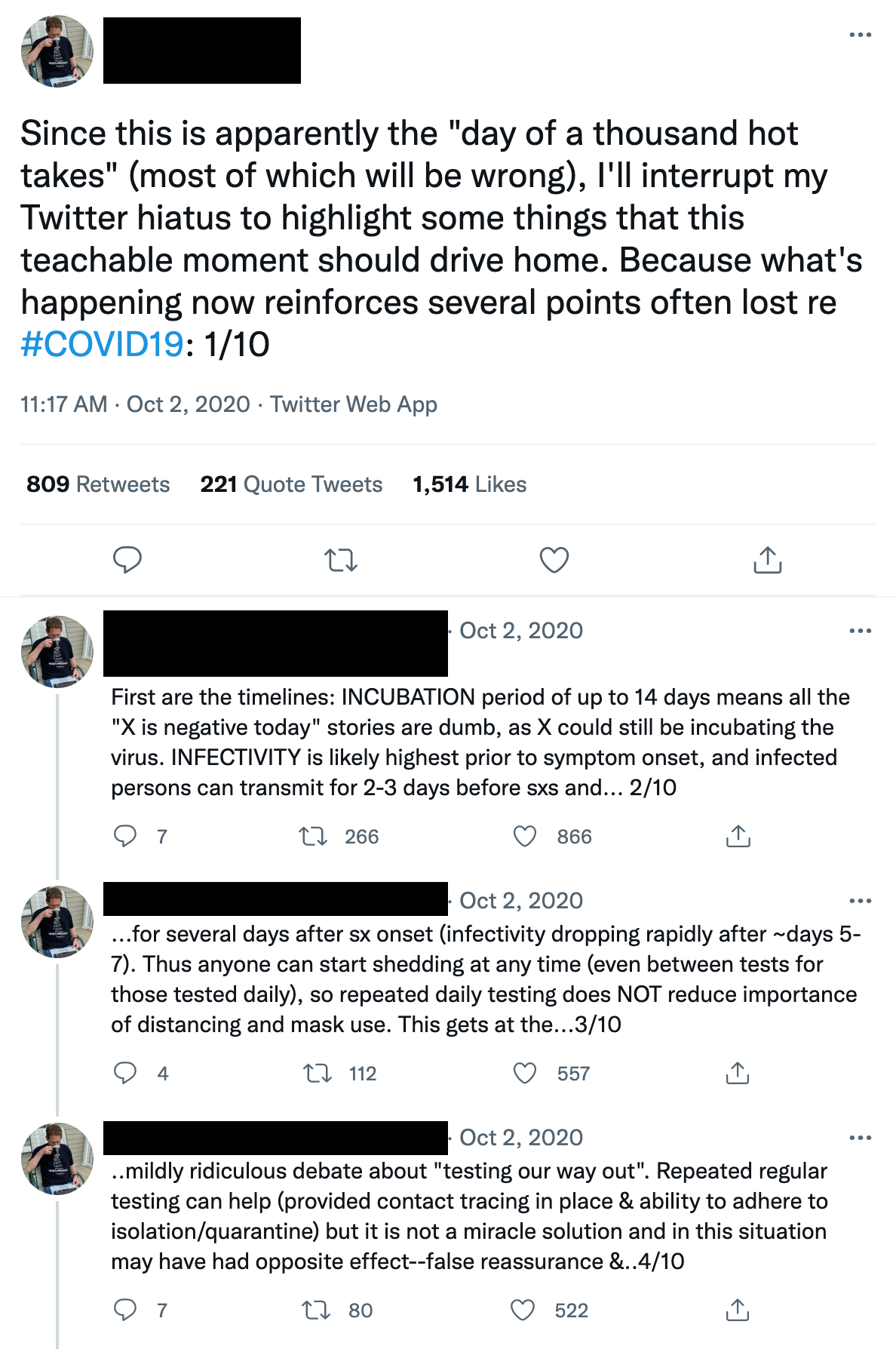

Those stressors intensified over the past year and a half, evolving somewhat differently for physicians and nurses, according to Dean Browell, a digital ethnographer and principal at Feedback, who has been tracking the issue of burnout online for years.

Browell

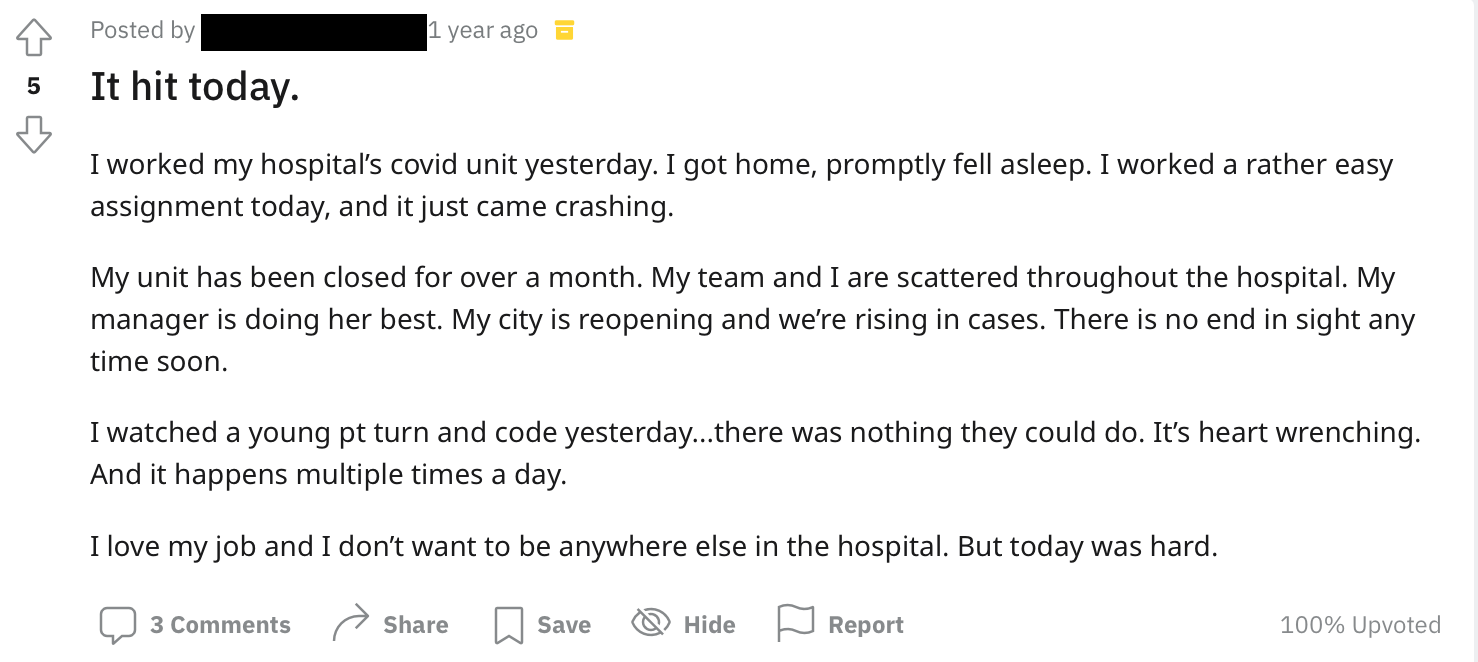

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve seen clinicians of all stripes joining the conversation online. That’s not new, but it has taken on a different flavor, per Browell. Nurses, he said, have long used digital platforms to discuss work-related issues amongst themselves. Early in the pandemic, those conversations expressed frustration with somewhat amorphous ideas of “hospital administration,” and the virus. Exhausted nurses were checking around for jobs that might give a bit of relief.

More recently, the anger has moved towards a more direct target in “the patients,” specifically the unvaccinated. That shift has led to more public activity among nurses, and the persona of long-suffering, patient caregiver is being replaced by that of the exasperated professional fed up with the parade of patients making dangerous choices.

Trauma is Changing the Equation (Permanently?)

Essentially, healthcare is facing a potential and troubling shift in the way caregivers see their roles.

Clinicians and their families have shared with us this refrain about their calling: “I’m putting those around me at risk to care for countless people who made choices that are creating the danger.” Dedicated nurses and physicians are having to decide how far that mission goes. And that tension is creating moral injury – possibly even recalibrating the moral and psychological standard.

An example one person offered: An ED team can treat the single gunman who’s harmed others, successfully managing their emotions and maintaining their oaths to care for every patient. Yet when a notable percentage of the population – healthcare worker and public alike – refuse to get vaccinated, it becomes like an accumulation of mini active shooters coming through the ED doors every day. And with that, a mental shift could happen that unconsciously allows the level of care slip.

Others maintain that the levels of care won’t suffer, but that there will be greater distance between clinician and patient. Those who make it through will become more aloof.

Holding on to “Heroes”

It’s time to stop using the language of “healthcare heroes.” It rings hollow and feels discordant with what’s happening inside ICUs today and the way a big chunk of the public is acting towards healthcare workers.

“About a year ago, this larger burnout effect started being stoked by the hero messaging that was finally starting to get a little stale. It was this idea that, ‘Hey, I’m tired of being a hero right now.”

– Dean Browell, Feedback

“Healthcare workers got at least an emotional boost by being the ‘healthcare heroes.’ That’s just not happening anymore. They are back out in their communities, and they see people walking around without masks. It’s disheartening. Same thing with treating anti-vax patients – it’s creating a lot of anger.”

– Lisa Bielamowicz, MD, Gist Healthcare

“The core issue today is staffing. It’s time to point out the problem, which goes beyond healthcare. It’s also a problem in any type of service job where society pays low wages to people who we call heroes on a daily basis.”

– Erika Matallana, Jarrard Inc.

Leaking from Both Sides of the Pipeline

Roades

The result of all this could be an exodus. It may play out in lower enrollment in nursing schools, as more early retirements or leaving healthcare mid-career. (While the American Association of Colleges and Nursing noted an increase in enrollment last year, Browell said he’s hearing from top-tier schools that are struggling to fill seats.)

“People have changed their calculus about where they want to be spending their time. Younger people have alternatives,” said Chas Roades, CEO and co-founder of strategic advisory firm Gist Healthcare. He pointed out, only somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that given the level of pay at entry levels in healthcare, some people may view warehouse or gig economy jobs as viable, safer alternatives. Lisa Bielamowicz, MD, president and co-founder at Gist, brought up the education debt issue for clinicians. “It’s hard to talk about aligning compensation and incentives if people have to take out a second mortgage for 20 years to pay for student loans,” she said.

Bielamowicz

Clinicians Have Options

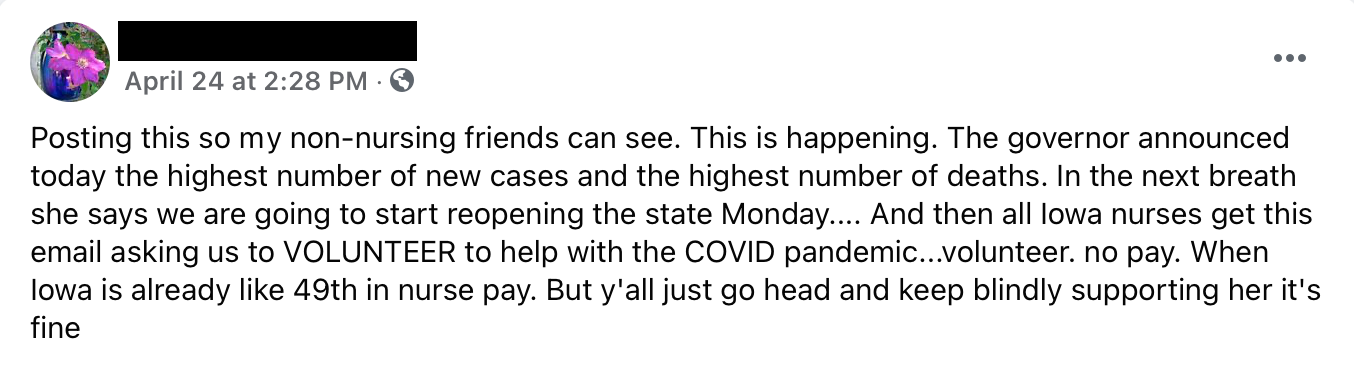

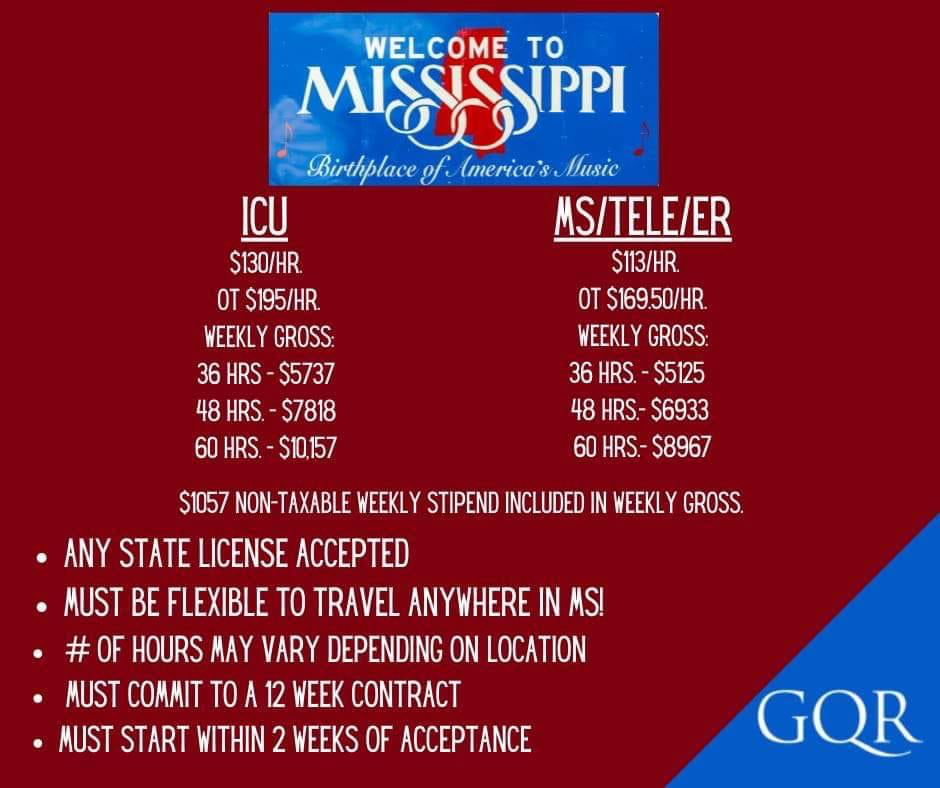

Between the rise of telehealth and the resurgence of concierge care, there are lots of career options today enabling clinicians to practice without having to deal with some of the mess. Physicians in particular have the financial resources to look around and find other revenue streams. For nurses, travel jobs have always paid well. Now, privately owned groups are offering massive pay jumps and impressive per diems for those inclined to take contracts – sometimes not far down the street from their current employer.

“They’re understaffed and their people feel at risk because the ratios are so high,” said Aaron Campbell, a Jarrard Inc. associate vice president keenly focused on patient and employee engagement work. “There’s a sense, too that the short-term solution – ‘I’m going to bring in people who’ll be paid far more than you and aren’t invested in our culture and will be gone in 12 weeks,’ – is going to create even more strife.”

Browell explained it by positioning traditional providers at the center of the industry and new models of care on the outer rings. It’s about how many people leave the center of it for “a nice, quiet CVS somewhere,” he said. There was already attrition for hospitals because of the rise of those new models. In the next 18 months the threat to traditional providers may increase because people don’t want to stand in the center of the storm.

Of course, the flip side of that is significant opportunity for health services organizations. Referring to an orthopedic group client, Browell observed, “Their story is going to be a fantastic one they can ride for a while because they can recruit a nurse who is desperate to get out of an ER by showing them what it’s like in an ortho urgent care by comparison.”

What’s the Answer to Burnout?

In our interviews, a near-universal sentiment is that this won’t be quickly fixed, only managed. We can only do so much to help clinicians and other employees who are at the end of their rope. The days of quick fixes ended years ago (though we do offer a few ideas for immediate intervention in the sidebar.)

Operationally, providers need to look ahead to long-term transformation. That could mean evaluating technology across your enterprise. Or creating a Wellness Office, which Michigan Medicine did before the pandemic. Or even going truly massive – how about HCA owning a nursing school? In contrast, some Communications strategies can be brought to bear immediately.

We don’t want to wait until people are in a crisis. We’re trying to understand the factors that are contributing and do something before it gets to that point.

Rose Glenn, Senior Vice President, Chief Marketing Officer, Michigan Medicine

Glenn

Operations

PURSUE STRUCTURAL CHANGE

First and foremost, don’t expect to paper over the shifts in healthcare. “Change can’t just be a rebranding exercise,” said Jarrard’s Campbell. He pointed to K-Mart’s promise to evolve several decades ago. They asked their employees to stick around and buy-in to that vision. Many did, literally. The company used pension funds to buy company stock, leading to huge losses and a lawsuit in the early 2000s. “People are trusting you,” said Campbell. “You have to pursue deep change to follow through on that.” We all know what happens to organizations that try to skip past the hard work and fail to adapt. (There are 33 K-Marts left, in case you were wondering.)

OFFER SHELTER FROM THE STORM

Clinicians are considering their career options. Many who want to stay in healthcare may look to move away from the center of the storm. When possible, Bowell says, providers should offer that.

Admittedly, this is easier for larger systems with opportunities for lateral moves within the enterprise, and frequently, larger coffers for salary increase and other investments. Health services companies like the orthopedic group mentioned above often can provide calmer environments. The challenge is greatest for smaller systems and independent hospitals. “For smaller hospitals, it may be about investment in telehealth and generally finding ways to be less reliant on ER/trauma,” said Browell.

OPEN YOUR WALLET

Which brings us to financial compensation for physicians and nurses. Money can’t solve all the problems for a mission-driven workforce, but financial incentives do need to better reflect the realities both nurses and doctors are dealing with. Some thinking:

- Imagine the tension in organizations where staff ICU nurses are working alongside travel nurses hired with huge stipends. Dollars should be wisely allocated for retention as well.

- Surprisingly, hazard pay hasn’t really hit the healthcare industry in a major way, but could be a solution as this plays out, noted Browell.

- Graepel, the early-career physician-scientist, put it bluntly: “Financial issues are a huge strain for many of my colleagues. Increased financial compensation would go a long way to lifting some of these major stresses. People are looking at a quarter million dollars in debt while getting paid $60,000 a year… It can be hard to imagine what that future looks like.”

So where does the money come from to fund this? After all, labor is already the largest cost for hospitals and health systems. Gist’s Roades suggested “looking at trade-offs with other expenditures like capital projects.”

Making Appreciation Apparent

Some of these can kick off tomorrow, others require a bit more time and investment. But all will give your team small yet meaningful doses of hope. As always, ask your team what they need – and what they don’t want to see. They’ll tell you.

Visual reminders of mission and appreciation

Hand-written letters to employees’ loved ones to express appreciation

Local media coverage highlighting employee service

Discounts/gifts from local businesses

Free subscriptions to wellness/mental health apps

Membership to services connecting people to daycare, pet care, handyman, etc.

Cover meal/grocery delivery service fees

Subsidized gym memberships or, better…

…Build/update a top tier on-site gym

Revised PTO to offer extra time off or create “PTO banks” for specific situations.

SUBSTITUTE, STRATEGICALLY

Technology can also help free up money for better compensation – along with saving time and reducing stress. First, more user-friendly EHRs are directly correlated with lower workload and, by extension, burnout. Second, is “strategic substitution” and job design – finally realizing the long-promised revolution where technology can augment the human touch and allow clinicians to practice at the top of their license. Bielamowicz and Roades were adamant that strategic substitution and streamlining operations from back office to clinical decision-making will reduce stress on the healthcare workforce and make more efficient use of limited dollars. Leaders should be asking if there are places to reduce dependence on labor by using AI or restructuring their teams so patients can do more self-service.

It’s always critical, our experts maintained, to evaluate human capital, asking if the right people are doing the right things and identifying gaps that need to be filled. “Everyone wants more data-driven, personalized care,” Bielamowicz said. “Every health system wants to take data from devices and use it for remote monitoring. But right now, we don’t have people to take that information and turn it into actionable information. We need medical technologists trained to do that work.”

Lastly, finding ways to accomplish back-office work related to revenue cycle and HR is not a new discussion. Those tasks are prime candidates for automation and AI to free up resources.