The Big Story: Barely half of physicians trust their leadership teams – Jarrard Inc.

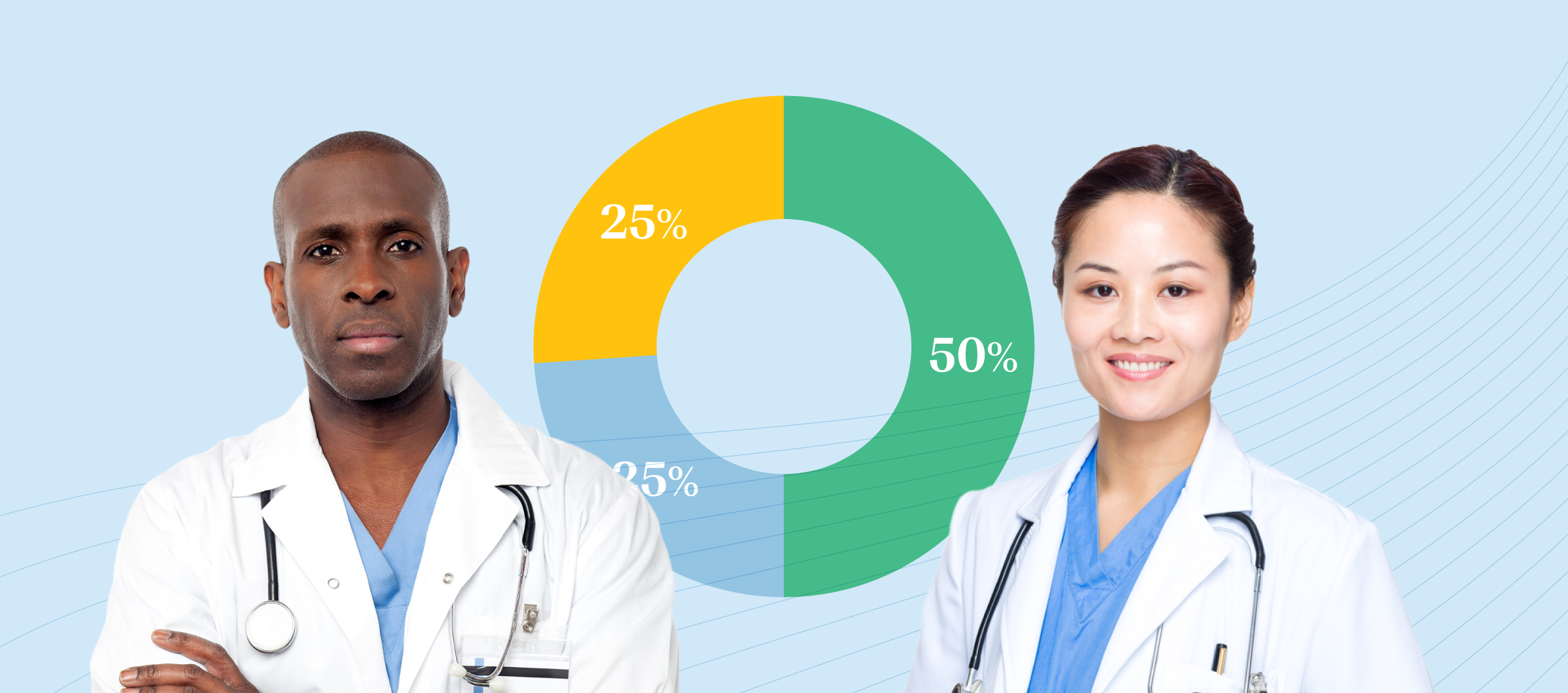

Only 50 percent of physicians nationwide say they have a lot or a great deal of trust that “The leaders of my organization are honest and transparent.” Only 53 percent say they have a lot or great deal of trust that “the leaders of my organization are making good financial decisions.”

How do you advance change if physicians don’t trust you? Short answer – you can’t!

By David C. Pate, MD, JD

4-minute read

The trust between physicians and healthcare leaders is the axis around which essential organizational change – and the transformation of our industry – will succeed or fail. As one who has practiced medicine and led a regional health system, I can vouch for that.

In a new survey of hundreds of physicians from across the country, Jarrard Inc. explored how physicians perceive the strength of their relationship with their organization and its leaders.

Turns out, they generally see it as fractured. Trust is lacking.

Not enough transparency about clinical goals and financial issues. A sense that organizations are “money hungry” while physician compensation is rising but not enough to keep up with inflation. Executive leaders aren’t visible and present. And they don’t appear to be “receptive to ideas and input from physicians.”

Despite best efforts by many, the connection between leaders and their physicians in today’s hothouse healthcare environment – in which the pressures are significant and relentless, the players are exhausted and great change is required – is often fraught.

Of course, your mileage may vary. For some, these national averages may be surprising. A wakeup call that not all is quite as rosy as hoped. For many others, the data isn’t remotely surprising, but merely confirms what was already obvious. The numbers may provide the wake-up call that the organization’s board and leadership team needs to make changes and address the underlying culture of the organization.

So, where do leaders go from here? Let’s use the Jarrard survey’s primary findings as a trailhead.

Finding: Physicians overwhelmingly want transparency.

In an open text question, one third of responses included the word “transparent” or “transparency.” Meanwhile, 25 percent have little to no trust that their leaders are honest and transparent.

Translation: Doctors understand that they’ll disagree with some decisions. What they want is to know what’s going on in the organization they’ve committed their professional lives to. And to be listened to and heard when they express their views. And to understand the reasoning for the decision.

Takeaway: Transparency is in the eye of the beholder. What’s substantial transparency to you may be seen as inadequate to your medical staff. Survey your physicians to gauge how transparent they think you are, then respond accordingly. Physicians understand that there are some things that you simply cannot share. However, they expect you to be transparent about the mission of the organization, the vision for the future, the strategic plan as to how the organization will get there, the quality and safety of care, the goals of the organization, the progress being made as to those goals and plans, plans for expanding or contracting services or service areas, the process for allocating capital – especially capital for clinical programs and technology.

Communicate plans in real time, delivering them via the messengers whom physicians trust and through the channels they prefer. Give regular updates, especially when there are bumps in the road. Physicians know that not every goal will be met or every plan be successful. You gain credibility and trust by being open and honest, both about successes, but also about failures. Provide opportunities for physicians to ask questions and offer feedback. Then report back on how your team is using that feedback so everyone knows they’ve been heard and included in the process.

Finding: Physician loyalty is fragile.

On a scale of one to five, one third of physicians say their level of loyalty to their organization is somewhere from one to three. That’s marginal loyalty or less.

Translation: If physicians don’t think leaders are loyal to them; they won’t feel loyal to the organization. What makes physicians feel that leaders aren’t loyal to them? Rightly or wrongly, it’s often the perception of unfair (and especially inequitable) contracts, unfair compensation and constant criticism that they’re underperforming or need to take measures to improve the financial performance of the hospital, without being given the resources to make those improvements.

Takeaway: Show that their priorities and mission are the same as yours. Caring for patients. Delivering quality care. Being a good employer and strong community partner. Show it by talking about clinical quality. About patient experience. About how the organization’s resources are being used to further its mission while acknowledging how those financial and operational decisions affect physicians. Show it, too, by providing context from peer organizations and industry information. Docs are scientists – they’ll appreciate data that buttresses the conversation and give them benchmarks to either celebrate exceeding or to focus on working towards.

Finding: Physicians trust their peers.

They also feel more loyal to peers. Physicians overwhelmingly picked “my physician colleagues” as their most trusted voices. And less than 20 percent express low or no loyalty to their teams.

Translation: This isn’t a surprise. It’s the same with nurses and, well, just about anybody who works anywhere. We all naturally trust those we work most closely with. In this case, physicians trust their peers because they all care for patients. They share the same concerns. What about leaders? Physicians don’t see them talking about patient care. They see them – or, more accurately, don’t see them – in their offices on computers or the phone or in meetings.

That lack of relationship plays out in lack of trust. Physicians don’t trust leaders they don’t know. Therein lies the work ahead.

Takeaway: First, work towards a culture that encourages and facilitates interpersonal relationships, not one that treats peer connection as a byproduct of working in the same room. Leadership should spend time with clinical teams understanding what their day-to-day looks like and, alongside your HR and professional development teams, create ways for physicians to have space to connect with their peers. You can’t force relationships, but you can open opportunities for them to develop.

Second, get to know your physicians. Walk the halls. Spend time on the units and in the clinics. Make sure your presence is known. You don’t get credit for your efforts by people who don’t see you or know that you were there. Don’t forget all those who support patient care, but are not in patient care areas. You and the executive team aren’t a nameplate on a door upstairs. You’re a person with a mission, striving for the same things as those caring for patients. People have to see you to know that. You should spend the majority of your time asking questions and listening, rather than talking. And, try to establish connections to their families and personal lives, not just their work.

Finding: Female physicians are more skeptical and less trusting than their male counterparts.

Male physicians are three times more likely to say the CEO of their organization is their most trusted voice (18 percent vs 6 percent for female physicians). While 70 percent of male physicians say they feel loyal to their organization, just over 60 percent of female physicians do. Only 42 percent of female physicians have confidence that their leadership team is honest and trustworthy. The average is shifted upward by male physicians at 55 percent.

Translation: CEOs aren’t doing enough to show respect to female physicians, listening to them (they often feel that their male counterparts dominate meetings and discussions), and being responsive to their needs. This is often strongly reinforced when the ranks of section chiefs, department leaders and executives are predominantly or almost exclusively male.

Takeaway: The need for equity applies to so many areas, including gender. One obvious push here is to diversify the leadership pipeline at your organization. In addition, make a concerted effort to seek out female physicians for feedback and needs assessments, and implement changes that enhance their experience. Do it because equity is a moral good. There are many instances in which new patients are seeking a female physician. Recognize that having diversity among your physicians allows you to widen your patient base. `And yes, there is also research indicating that female physicians have better patient outcomes. Strengthening your female physician population is a clinical quality benefit, too.

Crossroads: Choose Your Path

Whether these survey results confirm something you’ve long known from direct experience or are a shock uncovering previously hidden fault lines, they do create a chance to make a call. That is: Stay the course or double down on engaging with your physicians.

Stay the course – Push forward, confident in the current state of relationships between physicians and leadership teams. Allow the inevitability of market forces to push and pull strategy forward, then in turn pushing change onto physicians and others.

Chart a new course – Alternatively, measure and address the trust gap with physicians. Although it may seem awkward or uncomfortable, physicians, as a whole, don’t want you to assume everything is great. It may be, but they still want you to ask. Invest time and energy into a renewed conversation with your key physicians to bring them into partnership with you. Improve your visibility with staff and physicians. And, above all, make a focused effort on frequent, clear, meaningful communication with your physicians and other important stakeholders.

Either way, there’s hard work ahead, and none of it is without risk. But without your physicians, how do you fulfill your mission?

David C. Pate, MD, JD is an accomplished internist, lawyer and health system executive who also serves in an of-counsel role at Jarrard Inc. Dr. Pate is the immediate past president and chief executive officer of St. Luke’s Health System in Boise, Idaho. He joined St. Luke’s in 2009 following executive positions with St. Luke’s Episcopal Health System in Houston. He received his bachelor’s degree from Rice University, his medical degree from Baylor College of Medicine and his law degree cum laude from the University of Houston Law Center.

Contributors: David Shifrin, David Jarrard, Emme Baxter

Image Credit: Shannon Threadgill