The Big Story: Staffing, high costs jeopardize inpatient maternity services – Modern Healthcare

“For years, the U.S. has had the highest maternal mortality rate among developed nations, in part due to the lack of providers. Thirty-six percent of counties in the U.S. do not have obstetric providers or a hospital or birth center offering obstetric care…about 300 birthing units have closed in the last five years.”

The people who use healthcare the most may trust it the least.

By David Jarrard

4-minute read

Women are America’s healthcare power buyers.

They use more healthcare services than men, spend considerably more on it, and are the family shepherds who guide children, spouses and aging parents through our industry’s wearying maze even as they navigate their own complex care. Harvard calls women the Chief Medical Officers of the home.

So, the trust that women place in providers of care – or their lack of trust – matters. And it’s lacking. A lot.

Last week, we highlighted results from our latest national survey of 840 US adults. Now, we look at how women and men answered those same questions:

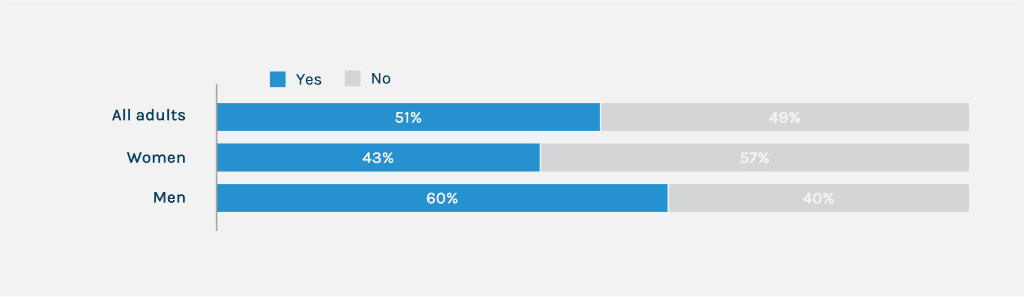

A landslide majority of women – 57 percent – say provider organizations don’t meet the needs of most Americans, compared to 40 percent of men.

“Do you believe hospitals, health systems and other organizations that provide medical care are meeting the needs of most Americans?”

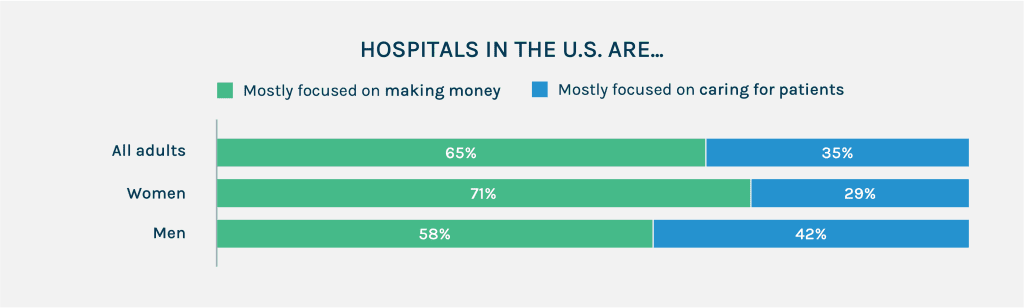

An extraordinary 71 percent of women – versus 58 percent of men – said providers are mostly focused on making money versus caring for patients.

“Whether you agree or disagree with each of the following statement, please select which one you agree with the most.”

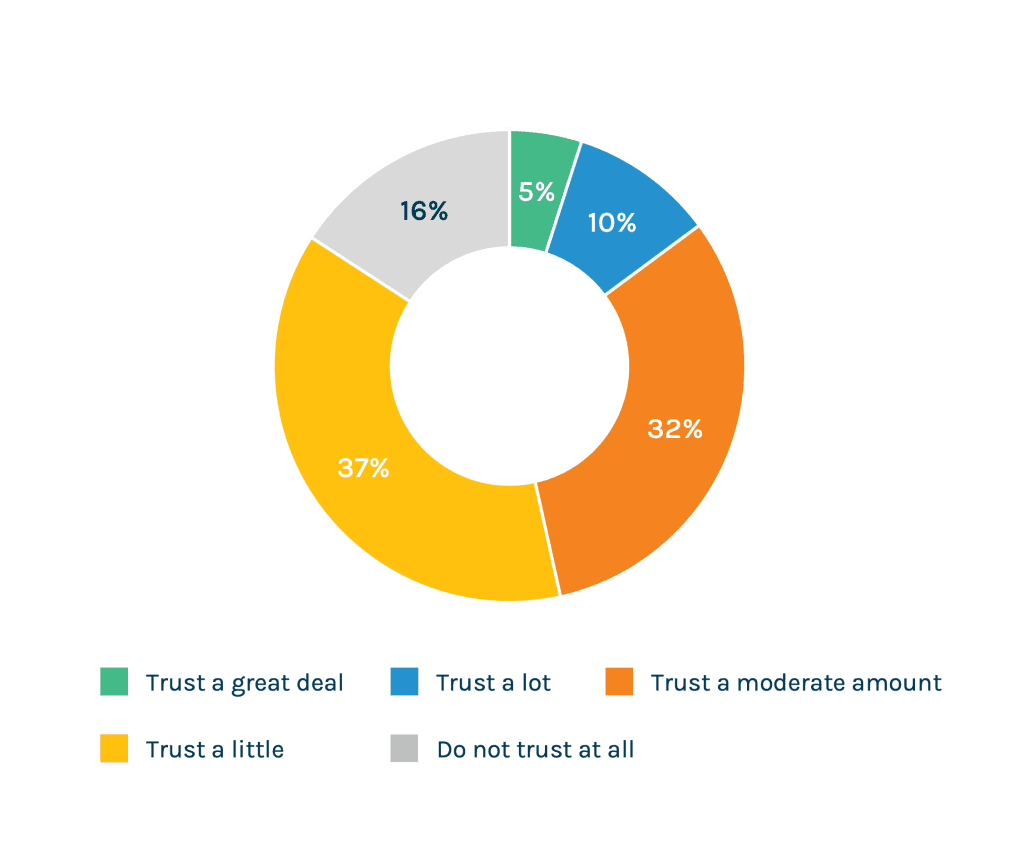

“How much do you trust health system leaders when it comes to making decisions about healthcare?”

When asked their level of trust in health system leaders and given a sliding scale between “do not trust at all” and “trust a great deal,” 53 percent of women chose the options to the left – trust just a little or not at all.

We’ve tracked for some time the erosion of trust in our broader culture, within the healthcare industry and, more lately, the emerging and significant consequences of this decline for providers.

While trust is low for most every demographic we tested, women were consistently one of, if not the, least trusting groups. It’s a keen political and marketplace vulnerability for providers to appreciate and an opportunity to address.

A “Pink Tax” on Healthcare?

There are myriad undercurrents issues burbling beneath these findings. We’ll suggest four in the broadest of strokes.

Healthcare costs more for women. The burdensome high cost of care is an issue for everyone. Even decorated Olympic gymnast Mary Lou Retton turned to crowdfunding to pay for her medical bills.

But two reports released earlier this month take a new angle on the decades-old concept of the “pink tax,” which refers to inflated prices applied to goods and services marketed to women. They explore what some say are endless extra out-of-pocket costs women must pay for their healthcare.

One report, says CNN, shows women who have health insurance through their jobs “pay about $15.4 billion more in out-of-pocket health care costs than men with similar insurance.” Another, from the Susan G. Komen Foundation, says that when it comes to breast cancer, the extra expenses are causing such a significant burden that it may be costing women their health.

America’s expanding maternal care crisis. In last week’s take on the issue, Modern Healthcare’s Caroline Hudson reported that “rural areas and critical access hospitals are typically the hardest hit by maternity care cuts.” The AHA, she writes, estimates at least 89 obstetric units closed in rural hospitals between 2015 and 2019, before COVID’s impact. The problem also extends to urban areas. Two hundred urban counties lost at least one obstetric unit between 2019 and 2020.

These are “maternity care deserts,” says the March of Dimes. In these places, “black women are nearly three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes compared to White women.” The rate of infant mortality (death) among Black babies is almost two times higher than the national average (5.4 per 1,000 live births).

The politicization of women’s health. In the year since Roe v. Wade was overturned, at least a dozen states have banned abortion entirely and more are seeking to further restrict access. The issue has become a political rallying cry. Along with the hot debates about gender affirming care, the politicized nature of women’s healthcare has remained visible, acerbic and polarizing.

Exhaustion with a system not built with the household CMO in mind. We offer no link to a third-party report on this point, but, instead, suggest that you can find corroborating case studies most anywhere. Ask a woman.

Here’s our own Abby McNeil, VP and deputy leader of our Regional Health Systems practice, on the question:

“Little or nothing about healthcare is designed for women, start to finish,” she says. “They have to call between 8:30 and 4:59 if they want to get an appointment. When they do, they have to take off work or haul kids to those appointments. They are saddled with making, keeping and remembering the appointments for everyone in their family and nagging them when they won’t go in for the care they need. They have to remember all the details, dole out the medicine and advocate for elderly loved ones who need care.”

And Teresa Hicks, VP and deputy lead of our National Health Systems practice:

“The reason we see women showing a more cynical posture toward healthcare is that if there’s frustration to be found within the healthcare system, it’s disproportionately women who are tackling it.

Women are the ones on the phone with insurance and the provider’s call center and then back to the insurance company to figure out why something wasn’t covered or why the medicine costs so damn much or why the blood test was sent to an out of network lab or what the hell is this facility fee on my bill. They’re doing hand-to-hand combat with the most dysfunctional parts of the industry while they’re trying to advocate for the people they love and are responsible for.”

On and on.

Everyone’s weary and women especially so. Gallup says the gender “burnout gap” has more than doubled.

“Women, whether they are in partnerships or not, whether those are equal or not, whether they have kids or not, are tired, especially of systems that add to the inconvenience of daily life,” McNeil says.

Maybe that’s a glimpse of one opportunity for healthcare providers in these findings – addressing the “inconveniences of life” through the experience of care you offer women and their families.

Addressing inconveniences…

If quality is a commodity, then thoughtful customer service that responds to the real-world needs of women is a differentiator. That new building you’re considering may be less important in the consumer’s mind than the always-on call center that can answer every after-hours request. To leave these issues unaddressed invites competitors to flank you.

You know how much women matter to your healthcare organization and why the loss of their trust is significant.

It’s not just the buying power. It’s political power, too. Women turn out to vote more often than men. As more elected officials pursue legislation to reduce reimbursements and otherwise dabble with healthcare, you need every vote and every voter on your side.

But it’s this, too: Women are the beating heart of healthcare delivery. Women are not only healthcare’s power users, they are its caregivers.

Three-quarters of the full-time, year-round healthcare workers in America are women, encompassing most nurses and a third of US physicians and surgeons.

As the US Census Bureau neatly sums up: Your healthcare is in women’s hands.

Contributors: David Shifrin, Emme Nelson Baxter, Abby McNeil, Teresa Hicks

Image Credit: Shannon Threadgill