“Mom, today I found out how I can own my own store.”

Was that the first thing you said as a teenager coming home after your first day of your first job slinging guacamole at a fast-food restaurant? Nope? Wasn’t for us either.

But that did happen to a teen whose orientation at Chipotle included a pathway to go from line crew to store manager to franchisee. And what a profound lesson for healthcare organizations struggling with staffing, said Dan Collard, co-founder of Healthcare Plus Solutions Group, who recently shared the story with us.

As Collard sees it: Recruitment starts with retention when companies give employees a reason to stay and grow.

Healthcare’s persistent workforce shortage is one of the industry’s most daunting issues right now. Everything’s on the table: large sign-on bonuses, retention bonuses, raises as everyone competes to staff up, whatever it takes. Many, especially rural hospitals, are barely hanging on. A few numbers to illustrate the point:

BY THE NUMBERS

Rural hospitals having difficulty filling nursing roles

Increase in salaries and benefits reported by HCA in 2021

Rural hospitals significantly increased reliance on travel nurses

Nurse leaders citing employee emotional health as key concern

We all know the problem illustrated by those numbers. But how did it get so complicated?

Social context. The great resignation is affecting every facet of the workforce, with retention of hourly employees particularly tenuous.

Damsky

Expectations for greater pay, better benefits, improved work-life balance, career development opportunities and a desire for a better connection with employers are leading employees to push for change and/or leave their position in pursuit of it. Nurses, techs and shared services employees are expressing those same expectations but with the added layer of the intensity of their work.

Different process. “How people are going about getting talent has evolved as nursing recruitment has been empowered by technology. That’s making it more costly and more competitive,” said Pamela Damsky, director and Performance Practice co-lead at Chartis.

Jung

Jeffrey Jung, engagement manager at Chartis, pointed to the rapid rise of placement firms and “matchmaking technologies” that help connect provider organizations with talent. Jung said the matchmaking software can increase the speed at which a nurse can be placed and make better matches on the front end to boost retention. “It’s cheaper than just using placement firms because of the technology, but the overall cost is increasing because there are so many more applicants being hired,” he said.

Jennifer O’Meara, senior digital strategist at digital marketing firm Eruptr,

O’Meara

said the recruitment campaigns her firm ran online before COVID-19 tended to be “as needed” and focused on RN recruitment. Now though, Eruptr is involved in comprehensive recruitment campaigns that run constantly across platforms. Budgets, she said, “are double and triple what we were running previously, and it’s not just SEM, it’s Facebook, it’s Instagram, it’s display ads, it’s YouTube… it’s everything.”

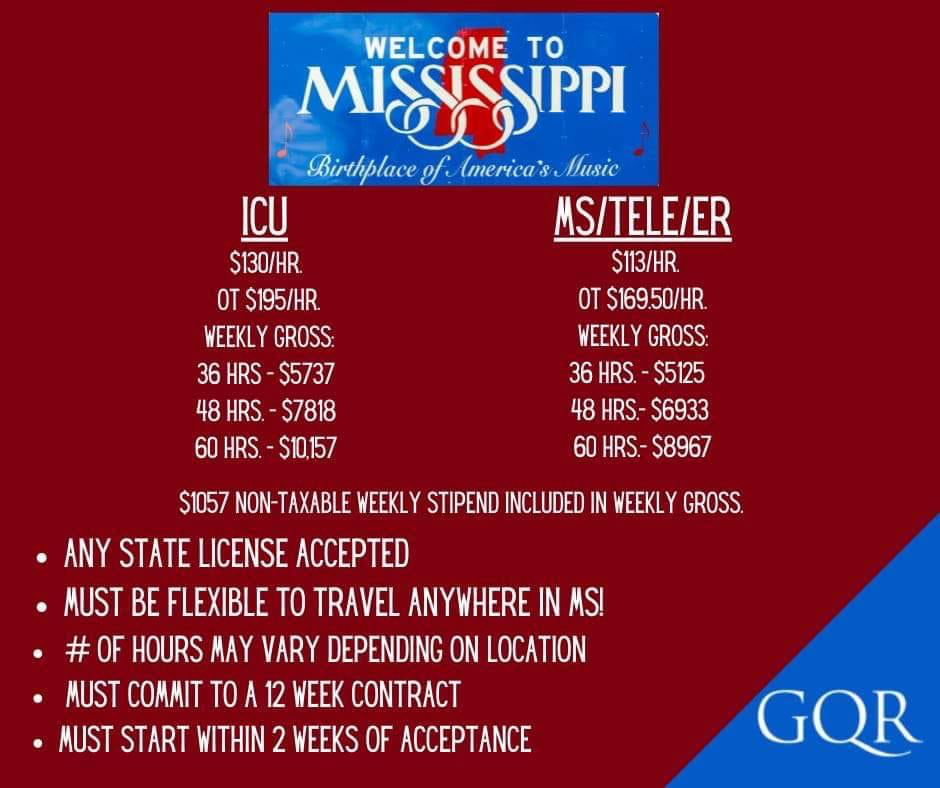

More competition. Atop increased cost due to shifting talent acquisition processes is the pressure to raise compensation through bonuses and higher salaries to compete with other organizations in the market for a smaller and, perhaps, more selective talent pool. Hospitals are vying for the same nurses and trying to fend off the travel firms. At the same time, nurses and other staff have far more options, with outpatient clinics and health services companies delivering outstanding care and offering attractive careers.

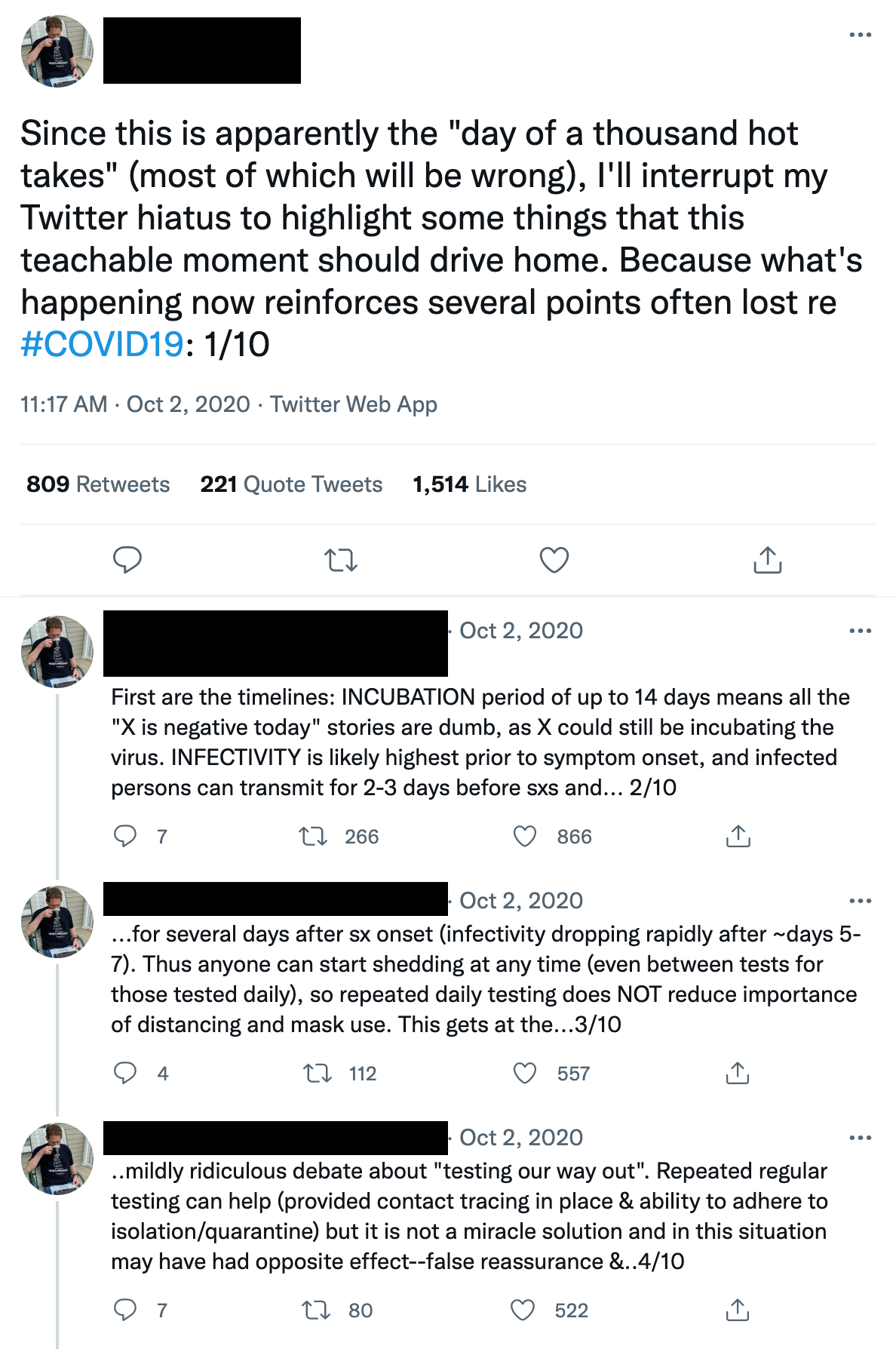

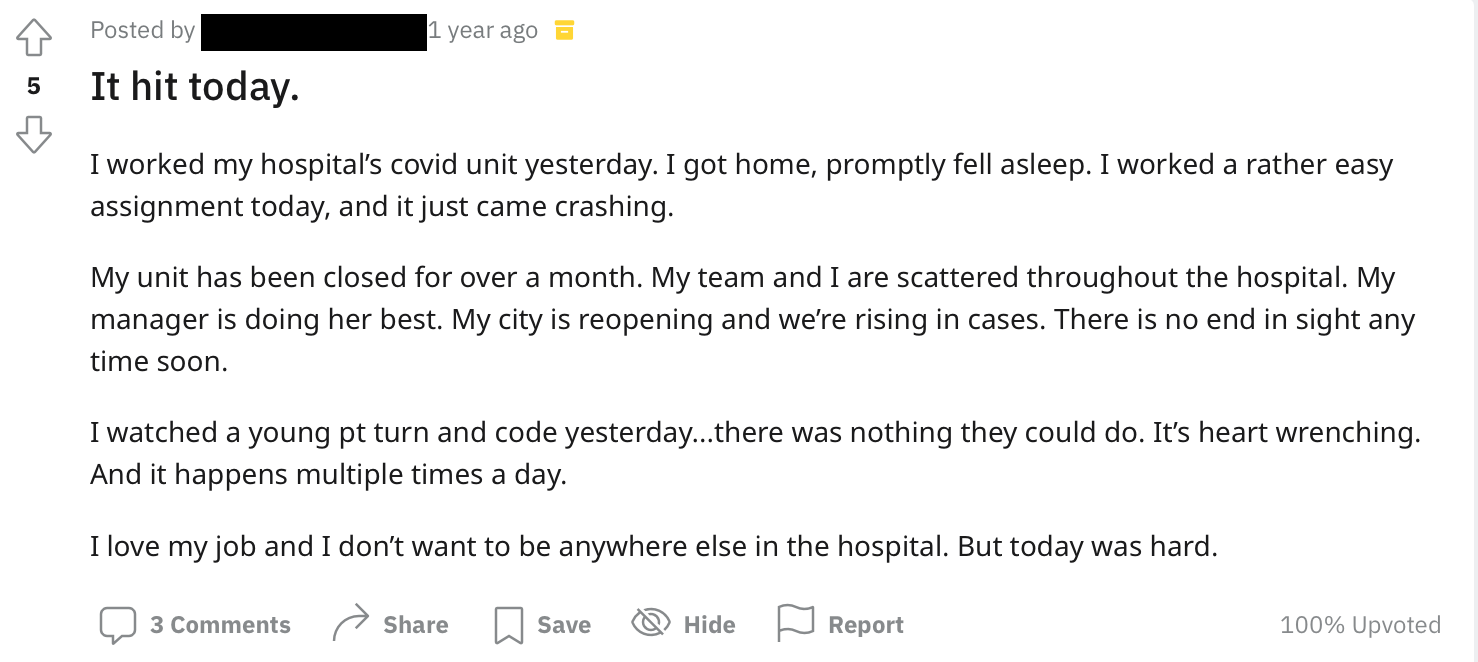

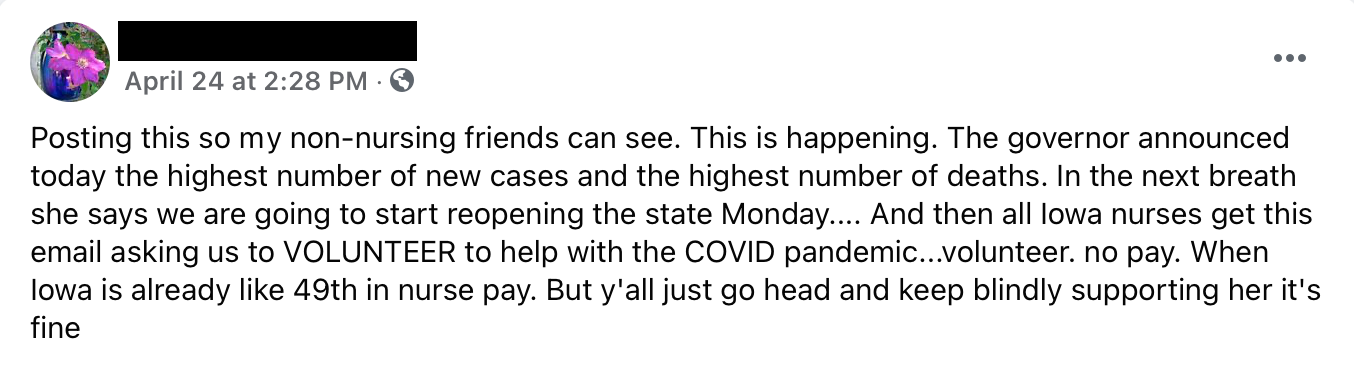

Frayed relationships. The pandemic has accelerated a breakdown between title bands. Leaders are working to keep the whole operation running, staff are keeping things clean and caring for patients, managers are liaising between the two. Nurses aren’t happy. They’re being asked to do more with less. The LinkedIn post from nurse Kelly Fassold illustrates it well. Fassold compellingly expresses the anger many nurses feel towards administration, regulators, hospital groups and anyone else trying to codify salary caps – or even just discuss nurse compensation. The relationship between administration and staff is broken, and nurses feel like they are – or actually are – on the outside looking in as discussions about their value take place. It understandably leads to the sentiment of being both disrespected and undervalued. “You’ve left us out of the conversation and you don’t understand what we do so how can you tell us what we’re worth?”

Surviving then solving the nursing shortage

The healthcare staffing crisis isn’t intractable, but it’s not going to be solved in the short term. Right now, healthcare execs and HR teams are doing whatever is necessary to have just enough staff on shift to deliver care. Whatever it takes. That only adds to the unsustainable feedback loop and the feeling that we’re in the middle of a land grab, making it that much harder to plan for the long term. But plan we must. In fact, we must redesign the whole thing.

To do that, we have to establish the environment for long-term change to take root. First, a few thoughts on the tactics hospitals and health systems can employ.

Current Tactics for Recruitment & Retention

Hospitals and health systems are activating a variety of strategies to staunch the bleeding of the workforce crisis. We’ve curated a list of short and long-term interventions in force today and arranged them by feasibility for different types of provider organizations. After all, very few health systems have the financial wherewithal to buy a nursing school the way HCA did with Galen College of Nursing nearly three years ago.

Remember that nursing challenges arise indirectly as well when other areas of the organization break down. Take environmental services. When that department is understaffed, nurses end up with additional responsibilities because who else will change the linens? It’s more rocks in the nurses’ backpack.

Collard referenced a health system that was struggling with retention among environmental services and other support staff. Leadership changed the employee onboarding process so that, instead of following up with new techs after 30 and 90 days, those conversations happened on days one and two. That kept new hires engaged and allowed managers to uncover questions and problems instantly rather than letting them fester, improving the likelihood that the individual would stick around.

Again, wise to stay vigilant on the indirect disruptions that spill over onto nurses and address them promptly.

Building a culture of retention

Our experts agree there’s no easy solution, and the hard, sustainable solutions involve completely rethinking how we deliver care. But then they cite something that absolutely can be accomplished: building a culture that makes people want to stay. And when people stick around, you save on acquisition and training costs, maintain workforce stability and naturally gain advocates who may recruit others.

But O’Meara cautioned: “If you have to talk so much about culture and sell people on it when recruiting, do you really have a good culture to begin with? Is that culture reflected once you get past the advertising and the recruiters who make you feel so great about everything? Is it reflected once a new hire gets into the clinical setting?”

Professional development

Collard

Back to guacamole. After telling the story of the young man’s first day at Chipotle, Collard drew the contrast with healthcare organizations. “On Day One, we’re more interested in getting people set up with their password for the electronic medical record and showing them which gloves to wear,” he said.

In the push to get people working on their floor as quickly as possible, there are so many priorities to check off the orientation list that nothing is a priority. In contrast, Collard asked rhetorically, what if hospitals were more like Chipotle? “What would it be like if we began to engage our clinical staff on the day they started?” He mentioned research findings that indicate nearly four of five millennials will take a job with lower pay if it’s a job they feel connected with and that provides them a clear career path. It’s not always about the money. (Although yes, the Chipotle post below does feature the money along with the career trajectory.)

Jung emphasized this point, too, but with less avocado and red onion. Before COVID-19 there was less enthusiasm for bringing in a new graduate “because they require so much hands-on involvement,” as he put it. That hesitancy to hire novice nurses and techs is changing, and what’s becoming important now for retention in a smaller labor pool is giving people a clear pathway to move and grow.

Carter

A specific example of this in healthcare comes from Dawn Carter, a veteran healthcare strategist and founding member of the Rural Healthcare Initiative. She said that from the moment they initially consider a healthcare career throughout their time with an organization, people need to see how they can grow in their job or grow into another one. Hospitals that are already helping finance additional technical/educational investments have a massive leg up – they should do everything to make those opportunities known.

Carter cited a speaker from the 2022 South Carolina Hospital Association meeting who suggested hospitals ensure that high school students understand the low-cost path to a high-paying job. Someone paying two years of technical college tuition and coming out of it with an RN can enter the market making $60,000, but there’s the potential for $200,000+ by pursuing a CRNA.

Another example? Take the entry-level hospital employees working in “central sterile” cleaning surgical equipment. The skill level is such that they could work at an Amazon warehouse for more money and skip the dirty equipment. Hospitals, Jung said, can and should create a defined career ladder for techs. Many techs are in nursing school, and if you create those relationships and provide the opportunities, they’ll eventually want to come back or continue employment when they graduate, he said. “It’s the difference between a very transactional, ‘We need you here’ and a relational, ‘We’re going to invest in you – and we’d love for you to go back to school,’” he said.

Nurse-manager relationships

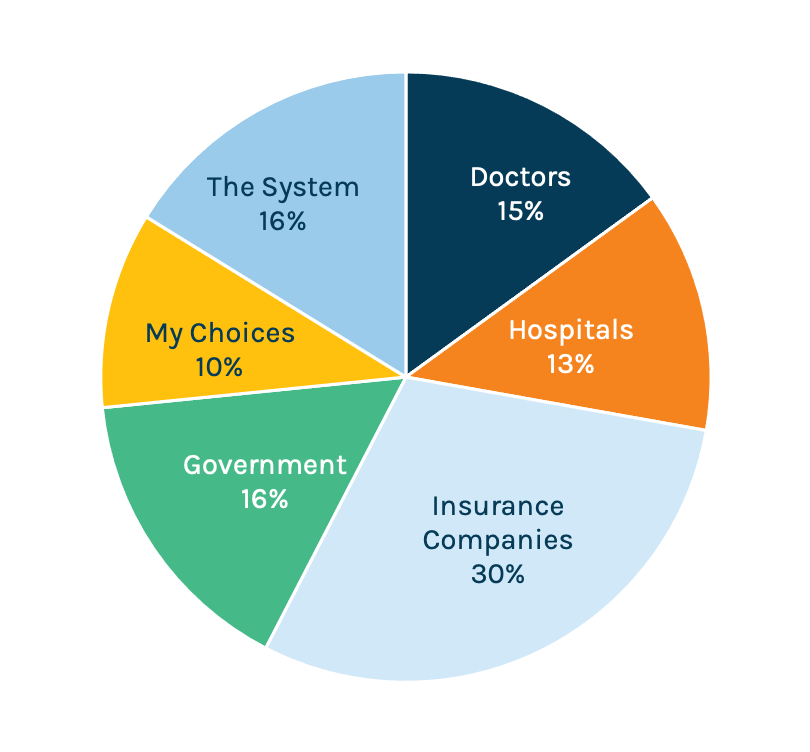

Go back to that LinkedIn post above. The post, and several comments below it, are built on the idea that unless someone has done the job they can’t know what it’s worth. It’s a push against salary caps, but it also reveals the significant gap between the suits and the scrubs. And it’s a fair point. The system is broken, staff see their census and patient acuity steadily increasing and the message many hear from managers and administration is a combination of, “Keep going,” and, “We can’t give you what you want.”

But again, sometimes what people want isn’t necessarily money. “We need to be sure we have salaries that match the market, but it’s more than dollars,” Damsky said. “It’s also treating nurses with respect and meeting their needs and creating an environment where they want to be.”

Carter highlighted the desperate need for leaders to spend time with staff, having heartfelt conversations about what they’re experiencing and humbly – not defensively – discussing leadership’s position on the issues and the various imperatives they’re balancing.

Sometimes it’s effective for managers and executives to share their own stories. We’ve heard from clients whose leadership spoke during town hall meetings about their toughest moments during the pandemic. Showing that level of vulnerability was powerful and helped dampen some of the tension that had been building.

Note that these conversations shouldn’t be used as distractions from or substitutes for practical interventions. They should be a supplement, a way to both solicit helpful information about what staff need and to demonstrate that the organization is working towards a collective solution.

Leadership development

Over the past couple of years, particularly during the omicron surge, we’ve seen an increase in non-clinical staff stepping in to help fill gaps. There are stories of managers running to get blankets, leaders helping empty trash. It’s certainly not happening everywhere or all the time, but more frequently than ever before.

That’s all well and good…but interestingly, our experts noted that it’s not necessarily the best thing. Plugging holes is an important crisis response and it’s great for showing staff that leadership is engaged, willing to do whatever it takes. Even so, there are drawbacks. “Leaders have been rolling up their sleeves and diving in,” Collard noted. “If I’m in that position, it means I’m spending less time leading and more time doing on the unit.”

Reconsidering Compensation

NOT EVERYONE WANTS TO BE A TRAVEL NURSE

— Nurse A 🖤🩺 (@Nurse_Lyss) February 5, 2022

We reference compensation throughout this piece and noted that it’s not always about the money. Two reasons for that:

- First, the key thing organizations should be providing people with is an environment that attracts them and keeps them engaged. Which, again, isn’t to say that our industry shouldn’t be taking a long hard look at financial compensation.

- Second, the current money isn’t sustainable – for anyone, but especially rural and independent facilities. The key is remembering that different people want different things, and any given organization can highlight the things it offers that will be attractive to someone, if not everyone.

According to Eruptr’s Jennifer O’Meara, hospitals in bigger cities with more competitive markets are relying more on bonuses and the financial incentives, while rural facilities and systems lacking competition but without the financial wherewithal are focusing on the intangibles. Think quality and cost of living. She said that in many recruitment campaigns there’s less emphasis on the standard “great culture” line and “a big push in online campaigns and in discussions about how making this move can be better for your quality of life.”

Cessna

Joel Cessna, Eruptr’s vice president of sales pointed out another example of alternative compensation for rural locations and those that can’t compete financially: creative benefits packages. For example, five weeks of vacation vs. three. “That’s a critical thing nurses are looking for, especially when you think about the exhaustion and burnout today,” he said.

Organizations need to find ways to get leadership out of staffing and back into leading, while equipping them to lead effectively. It’s the management version of practicing at the top of one’s license. It doesn’t mean someone never steps in to do something that isn’t in their job description. It means they’re doing their best so that they can help those in their care and on their team do their best.

“Leadership development becomes really important,” said Damsky. “It’s the thing that falls by the wayside because who has time for it?” There’s a cost when leadership development is put on the back burner and, conversely, a clear benefit when it’s maintained. Damsky mentioned a client who tracks employee engagement against their organizational development work. “They ask questions like, ‘Does my manager make me feel valued?’ and track that against staff turnover. They’re looking for negative correlation,” she said.

Helping staff feel valued involves moving leader rounding beyond checklists and perfunctory appearances. Collard said that it’s training leaders and giving them the space to have relationship-centric conversations. He said, “So when a leader says, ‘How are you doing?’ it means, ‘I’m not just asking, I’m really interested. It’s just me and you right now. How are you? What do you need?’” Collard cited a large medical center where a high-caliber ER nurse quit suddenly. When the team did some digging, they found out she hadn’t left for an agency to make more money. Instead, there were things at home affecting her ability to stay at the hospitals. Per Collard, the nurse executive said, “Oh my gosh, if we’d only known, we could have done something to help her!”

Eventually, healthcare provider organizations will be able to shift some of the focus from the crisis of filling shifts to the long-term structural change that will make staffing far easier. Many had laid such groundwork pre-COVID. And there is an array of remarkable health services companies rolling out software and innovative care models to solve the problem. Artificial intelligence, remote nursing, hospital at home, standardizing meal prep across a system, automated revenue cycle – everything that will put nurses and staff in a position to do what they do best and offload much of the rest.

We’re not there yet, but the foundation is in place and the frame is starting to take shape. In the meantime, provider organizations must step back to ensure that even as they continue the necessary scramble to fill shifts, they’re laying the groundwork. That means giving everyone in the organization permission and practical support to keep going. Starting on Day One.

A Note on Nursing Labor

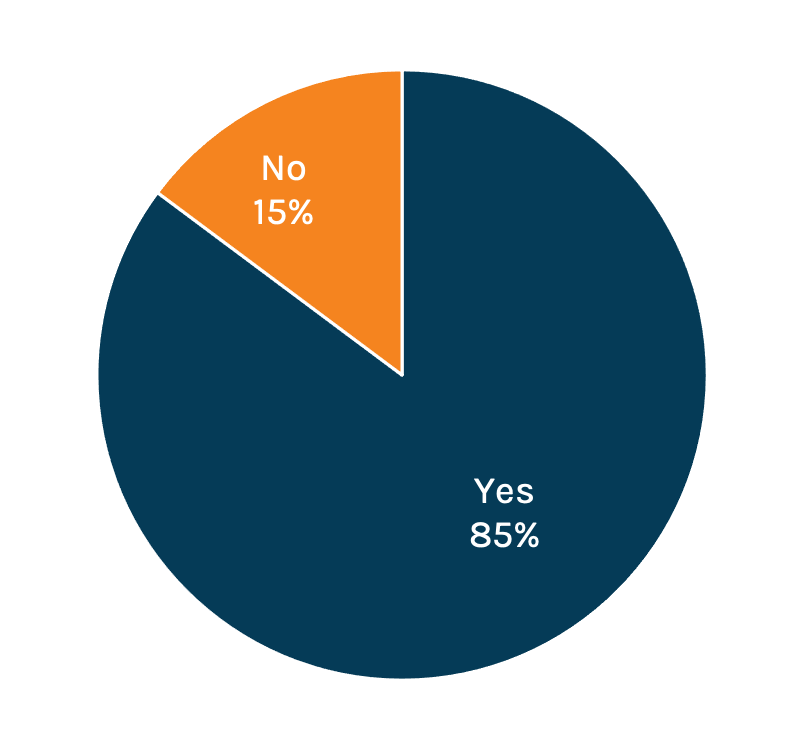

Nurses unions have been talking about staffing levels and compensation for years. Now, the conversation has come to them. Hospital advocacy groups could push back saying that it didn’t make sense to implement rigid staffing requirements; organizations of different types and sizes and locations needed flexibility. But on the heels of the pandemic, staffing has become a core concern, both among the public and healthcare workers – a point proven by the most recent Jarrard Inc. national survey.

The public citing staffing shortages as a top concern

Healthcare workers citing staffing shortages as a top concern

In addition, the business side has come to the forefront, and with it a rising skepticism among nurses and staff about the intentions of their employers. Some feel organizations are holding patient care over nurses’ heads while, in the background, pushing the business forward. The response is essentially: “We can’t be the only ones carrying the weight of our mission. If you expect us to be the only mission-driven people, we’ll go travel or organize and strike.” In addition, the employee-manager relationship is starting to ring hollow. Historically, a core argument against organizing is that a union only adds complexity, getting in the way of those direct conversations. But more and more nurses are feeling – or recognizing – that they don’t actually have that relationship and their voice isn’t valued. In that case, they’re not giving anything up by bringing in a third party.

There’s no easy fix for provider organizations. The solution is long term – doing the slow, hard work of engaging employees, giving them a real voice in conversations and training leadership to lead effectively. Before making any statement about valuing nurses’ input or taking any action to ostensibly boost engagement, ask whether the move represents a true, long-term commitment or is simply lip service, an attempt at a quick fix. Worried about organized labor? Give people a way to not need that third party.

Questions about employee engagement? We can help.

Sources for By the Numbers

Subscribe to Jarrard Insights & News

"*" indicates required fields